Ancient and Modern Sources

A selection of works that retell Penelope’s story

Homer The Odyssey

The Odyssey is an ancient Greek poem known as an epic, which probably emerged some time towards the end of the 700s BCE, a period of historical time known as archaic Greece. The Odyssey is part of what is sometimes called the ‘epic cycle’, which is a series of poems telling stories from the distant mythic past. The cycle includes many poems that have now disappeared, but there remains one other very famous epic poem from the cycle that is attributed to Homer: The Iliad. As an epic poem The Odyssey is defined by a few specific characteristics. To begin with, it is very long: about 12 000 lines, divided into 24 sections known as ‘books’, because they are the length of an ancient book scroll. The Odyssey is about heroic characters and actions, though what exactly defines a ‘hero’ is not all that straightforward. Technically Odysseus is a hero who is triumphantly returning from fighting in the Trojan War and trying to achieve a successful homecoming (nostos). He is exceptionally clever and persuasive, and he is a good warrior (though not the best), but he is also scarred by war, suspicious of others, violent, and ultimately loses all his comrades in his ruthless determination to get back to his palace, people, and property on the island of Ithaka. Even once he reaches home and reconnects with his son and father, he must then face new conflicts on the domestic front - conflicts in which the wife he left behind, Penelope, is implicated, along with the young enslaved girls of the palace.

In The Iliad one of the heroes, Achilles, is described as playing the lyre and singing of the ‘famous deeds of men’ (klea andron) - it is often assumed that this is a description of someone performing an epic poem. And this brings us to one of the most interesting things about The Odyssey. It was not composed and written down simultaneously, the way most modern writers work. Instead it was created over decades, even centuries, by generations of bards - a bard being a crossover between a musician, poet, and singer. We do not know who ‘Homer’ was, or if he (or she) even existed. All we know is that the strict 6-beat rhythms (‘dactylic hexameter’), repetitive formulae and refrains, and mixed dialects of the poem come from a long tradition of what is called ‘oral composition’ in performance. This is a process that is not unlike how modern jazz musicians improvise new versions of canonical works every time they perform.

Prof. Emily Wilson, from the University of Pennsylvania, has produced a very learned and popular recent translation of the Odyssey. She has also written some thoughtful and accessible articles about the poem, and about her translation process. Here she introduces the poem, with some useful reflections on what ‘homecoming’ means in The Odyssey. Wilson draws out how the poem is not, in fact, only about the hero Odysseus, but about how he interacts with a whole other group of people, and in particular how he negotiates the demands of archaic Greek hospitality to strangers (xenia).

On Wilson’s website you can find the links to her YouTube performances of each book.

Wall painting of Odysseus and Penelope, Pompeii

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penelope#/media/File:Fresco_Macellum_Pompeya_06_(cropped_to_scene).jpg.

This image is a wall painting found in the public market place of the Roman city of Pompeii. It was probably painted soon after 62 CE.

The seated Odysseus is still in his disguise as a beggar, while Penelope is wearing elegantly draped clothes. Odysseus and Penelope are cautiously looking at each other, while someone (one of the enslaved girls, maybe?) peers over Odysseus’ shoulder. Penelope in particular is sizing Odysseus up very thoughtfully, 🤔 perhaps trying to decide whether she can trust him or not.

Ovid Heroides 1, Penelope’s letter to Odysseus

Heroides are Latin poems written by a Roman author called Publius Ovidius Naso (‘Ovid’), who lived from 43BCE to around 18CE. Ovid is most famous for writing witty love poetry, and for his long retelling of hundreds of Greek myths in his epic poem called Metamorphoses.

In Heroides Ovid combines his main poetic interests, by imagining what mythic women were thinking when they were facing obstruction or conflict in their love lives. He decides to choose a particular moment in a dramatic story from myth, and then considers what the main heroine would have written if she had been able to write a letter to her lover at that point.

It was a fascinating - and highly innovative - decision to write poetry in the form of a letter. On the one hand ancient letters have sometimes been identified as quite a feminine mode of writing: they are a way in which women can communicate from the home to which they may be confined, and they are individual, private exchanges that do not take up vocal space in public. Many of the mythic scenarios that Ovid captures involve women trapped in a passive domestic situation.

On the other hand the women of Heroides are all exceptional characters, like Medea, Helen of Troy, or Dido the Phoenician queen of the Carthaginians. In fact these women go beyond their traditional mythic roles, in the sense that their letters allow them to resist the (often sticky) endings that await them in other canonical literature. They challenge readers’ expectations, and they get to explain and justify their motivations in an oddly informal, conversational mode.

The first of Ovid’s Heroides is a letter from Penelope to Odysseus. Twenty years have passed since Odysseus left Ithaka for Troy. Penelope is middle-aged with father-in-law (Laertes) who has withdrawn from society and a 20-year-old son (Telemachus) who was only a baby when Odysseus left. Telemachus has just returned from his own journey to mainland Greece to try and find out what has happened to Odysseus.

Meanwhile Penelope has had to cope with an influx of men from local islands, all competing to marry her for the power and wealth that Odyssey appears to have left behind. In this letter Ovid imagines Penelope’s pent-up anxiety and frustration. Indeed, Penelope suggests that this is just one of many letters she has been writing and sending off with every visitor who comes to Ithaka.

In almost all of his poetry, Ovid wrote in what are called ‘elegiac couplets’. The first line of an elegiac couplet has 6 beats, like in ancient epic poetry, but the second line has 5 beats. This creates a lilting rhythm that keeps a reader on their toes! Ovid likes to use the couplet to structure his thoughts, so his phrases tend to be quite short and snappy; often the second line of a couplet can have the feel of a punchline. In my translation below I (Emily Pillinger) have kept the two-line patterning, though without the strict 6 / 5 rhythm. Instead I have tried to keep the light, chatty tone of the letter. Penelope is fed up, but she is not a drama queen.

-

Ulysses, your Penelope is sending you these words. You are so slow!

Don’t bother replying to me, just come home.

Troy must be in ruins by now, the city that is hated by Greek girls.

The whole of Troy, and King Priam – were they really worth it?

I wish that Paris, when he first sailed to Sparta with his fleet,

had been swallowed up by the wild seas. The homewrecker!

I would not have had to lie in an empty bed, cold and abandoned,

nor would I have complained that the days passed so interminably,

nor would the hanging threads of my loom have worn out my grieving hands

as I tried to cheat my way through the endless nights. 10

Have I ever stopped fearing dangers, worse in fiction than fact?

Love is always full of worry and anxiety.

I used to imagine your Trojan aggressors on the attack,

I would turn pale at the very mention of Hector.

If anyone told the story of Antilochus being conquered by our enemy,

Antilochus became the reason for my anxiety;

If they told of how Patroclus had been killed while faking it in Achilles’ armour,

I sobbed over how his deceit could have failed.

Tlepolemus had warmed Sarpedon’s Lycian spear with his blood;

so my worries were renewed by Tlepolemus’ death. 20

Basically, whoever had been murdered in the Greek camp,

my loving heart turned colder than ice.

But the god that rewards faithful love took good care of ours:

Troy was reduced to ashes, and my husband survived.

The Greek leaders have come home, the altars smoke with celebrations,

looted foreign treasures are offered up to native gods.

Brides bring offerings in thanks for their husbands’ safe return;

their husbands sing of how Troy’s destiny was sacrificed for theirs.

Both rational old men and scared young girls are united in awe,

while wives hang on every word that is uttered by their husbands. 30

When the table is laid, one such veteran replays the fierce battles,

and paints with a drop of wine a whole map of Troy.

‘This is where the river Simois ran, this is the promontory of Sigeum,

here the magnificent palace of old Priam used to stand.

Achilles’s tent was over there, and Ulysses’ was over there;

here is where Achilles let his horses bolt in terror with Hector’s mutilated body.’

Well, the aged Nestor relayed all this information to Telemachus, your son,

when he was sent to look for you, who then passed the updates on to me.

He also relayed how Rhesus and Dolon were murdered,

one betrayed in his sleep, the other by deception. 40

Apparently you dared to enter the camp of Troy’s Thracian allies in a nighttime deception,

– far, far too forgetful of your nearest and dearest –

and slaughtered countless men in the attack, with the help of just one other soldier!

Still, you were careful, and kept me at the front of your mind.

My heart was pounding with fear right until you were said to have made it

back to friendly troops – a conquering hero, with the Thracians’ horses!

But how does it help me that your biceps have ripped Troy

apart, and that there is razed ground where there were once walls,

if I am left waiting, just as I was left waiting while Troy still stood,

and my husband remains missing, mourned, with no end in sight? 50

Everyone says that Troy’s citadel has been destroyed, but it still exists for me,

though conquering colonisers are ploughing the land with enslaved oxen.

Now there are fields where Troy used to be and the land needs hacking back with a sickle,

as it is so lushly overgrown; it has been fertilised by Phrygian blood.

Men’s barely-buried bones are being uprooted by curved ploughs,

weeds conceal ruined homes.

You are a conqueror, and hard-hearted, but you are missing, and I am not allowed to know

why you are delayed, or where in the world you are hiding.

If anyone anchors a foreign ship in our harbour,

I question him endlessly before he leaves, 60

and give him a letter written by my own hands

to give to you, if he ever sees you anywhere.

We have sent to Pylos, to the Neleian lands of ancient Nestor,

but the news sent back from Pylos is vague.

We have also sent to Sparta; Sparta doesn’t know the truth either.

Where are you living? Where are you not? You are so slow!

Frankly, it would be easier if Apollo’s Trojan walls were still standing.

(Yes, I know, I’m contradicting what I used to pray for!)

At least I would know where you were fighting, and I would only fear the battles,

and my endless complaints would be shared with those of other women. 70

As it is, I don’t know what to fear; instead I crazily fear everything,

and the world is an empty slate for all my worries.

Whatever dangers there are at sea, whatever dangers there are on land,

I imagine that they could be the reason for such a long delay.

While I’m stupidly panicking about these dangers, you may have fallen

in love with a foreigner. It wouldn’t be untypical for a man like you.

Perhaps you even tell her what an uncivilized wife you have,

who doesn’t care how rough anything is, except her wool for weaving.

No! I’m wrong! Let such a horrific notion vanish into thin air;

you couldn’t be staying away deliberately, if you were actually free to return. 80

My father, Icarius, has been pushing me to leave this empty marriage

and is always ranting and raving about my endless delays.

Let him rant as much as he likes! I am yours, and I should be known as yours;

I will always be ‘Penelope, wife of Ulysses’.

In fact I have worn him down with my loyalty and my measured appeals

and in turn he has been more restrained and calmed himself down.

Now I am besieged by a greedy mob of suitors, men from local islands:

some from Dulichium and Sami, and others from the high mountains of Zacynthos,

and they hold absolute power in your palace with nobody to stop them;

they are tearing apart your wealth – and my heart. 90

Is there any point telling you of Pisander, and Polybus, and awful Medon,

and the grasping hands of Eurymachus and Antinous

and the others? Your absence means you are feeding them all

with resources that you built up with your own blood. The shame.

And the ultimate humiliation: the beggar Irus, and Melanthius

who drives your goats out to pasture, must be counted as collaborators.

We are only three in number, and not exactly fighters: a wife without strength,

Laertes, who is an old man, and Telemachus, who is just a boy.

Indeed recently he was very nearly stolen from me through a plot

as he was preparing to travel to Pylos, though nobody wanted him to go. 100

I just pray that the fates proceed in the right order, and that the gods

make sure that he gets to close my eyes in death. And yours too!

Standing with us is our cowherd, and your elderly nurse,

and the loyal caretaker of the muddy pigsties makes a third.

But Laertes is not capable of ruling, as we are surrounded by enemies

and he is useless in battle.

Telemachus will become stronger as time passes (as long as he can stay alive);

but now is the time when he needs his father’s protective support.

Nor am I powerful enough to drive away our enemies from the palace.

You must come quickly; you are our rock, our safe space. 110

You have a son (I pray that he survives), at a vulnerable age,

who should have been taught his father’s skills by now.

Consider Laertes: he is staving off his last day of life

in the hope that you will return to close his eyes in death.

As for me? Even if you came back right now, you would find me

an old woman, though I was a young girl when you left.

Margaret Atwood The Penelopiad (Canongate, 2005)

The Penelopiad has been one of the strongest influences on Jeanne’s writing for ‘Penelope’s Web’. The novella places Penelope in a murky Underworld, giving her free rein to reflect on her experiences in the Odyssey. It is clever, allusive, contemporary, and without preaching it explores the misogyny of the Odyssey, particularly the harrowing fate of the displaced, enslaved women who are hanged at the end of the epic for having collaborated with the suitors.

Penelope speaks in a dry, cynical prose that is typical of Atwood. But because Penelope is a disembodied ghost in the Underworld, her prosaic voice sounds nothing like the sonic world that she describes. ‘Those of you who may catch the odd whisper, the odd squeak, so easily mistake my words for breezes rustling the dry reeds, for bats at twilight, for bad dreams’ (4). In trying to counteract the canonical telling of her story she says: ‘Don’t follow my example, I want to scream in your ears – yes, yours! But when I try to scream, I sound like an owl’ (2).

Meanwhile, though Penelope’s own words are consistently sour, the shape-shifting of the enslaved girls’ ghosts facilitates a range of poetic ‘choruses’ in different tones. Penelope herself recognises this. ‘They had lovely voices, all of them, and they had been taught how to use them…They were my most trusted eyes and ears in the palace, and it was they who helped me to pick away at my weaving… We told stories as we worked away at our task of destruction; we shared riddles; we made jokes… We were almost like sisters…’ (113-4).

The girls evoke a range of different, vivid soundscapes, including nursery rhymes, sea shanties, lullabies, courtroom speeches, and tape recordings. In other words, the novella seems to invite a musical reading, or even telling, of these women’s stories. The very last chorus has the girls sprouting wings and hooting like the owl that Penelope had described as her vocal call: ‘too wit too woo’ (196).

You can find an essay about the novella here by Issy Craig-Wood, a King’s undergraduate student.

-

Now that I’m dead I know everything. This is what I wish would happen, but like so many of my wishes it fails to come true. I know only a few factoids that I didn’t know before. Death is much too high a price to pay for the satisfaction of curiosity, needless to say.

Since being dead - since acheving this state of bonelessness, liplessness, breastlessness - I’ve learned some things I would rather not know, as one does when listening at windows or opening other people’s letters. You think you’d like to read minds? Think again.

Down here everyone arrives with a sack, like the sacks used to keep the winds in, but each of these sacks is full of words - words you’ve spoken, words you’ve heard, words that have been said about you. Some sacks are very small, others large; my own is of a reasonable size, though a lot of the words in it concern my eminent husband. What a fool he made of me, some say. It was a specialty of his: making fools. He got away with everything, which was another of his specialties: getting away.

He was always so plausible. Many people have beleived that his version of events was the true one, give or take a few murders, a few beautiful sedutresses, a few one-eyed monsters. Even I believed him, from time to time. I knew he was tricky and a liar, I just didn’t think he would play his tricks and try out his lies on me. Hadn’t I been faithful? Hadn’t I waited, and waited, and waited, despite the temptation - almost the compulsion - to do otherwise? And what did I amount to once the official version gained ground? An edifying legend. A stick used to beat other women with. Why couldn’t they be as considerate, as trustworthy, as all-suffering as I had been? That was the line they took, the singers, the yarn-spinners. Don’t follow my example, I want to scream in your ears - yes yours! But when I try to scream, I sound like an owl.

Of course I had inklings, about his slipperiness, his wiliness, his foxiness, his - how can I put this? - his unscrupulousness, but I turned a blind eye. I kept my mouth shut; or, if I opened it, I sang his praises. I didn’t contradict, I didn’t ask awkward questions, I didn’t dig deep. I wanted happy endings in those days, and happy endings are best achieved by keeping the right doors locked and going to sleep during the rampages.

But after the main events were over and things had become less legendary, I realised how any people were laughing at me behind my back – how they were jeering, making jokes about me, jokes both clean and dirty; how they were turning me into a story, or into several stories, though not the kind of stories I’d prefer to hear about myself. What can a woman do when scandalous gossip travels the world? If she defends herself she sounds guilty. So I waited some more.

Now that all the others have run out of air, it’s my turn to do a little story-making. I owe it to myself. I’ve had to work myself up to it: it’s a low art, tale-telling. Old women go in for it, strolling beggars, blind singers, maidservants, children – folks with time on their hands. Once, people would have laughed if I’d tried to play the minstrel – there’s nothing more preposterous than an aristocrat fumbling around with the arts – but who cares about public opinion now? The opinion of the people down here: the opinion of shadows, of echoes. So I’ll spin a thread of my own.

The difficulty is that I have no mouth through which I can speak. I can’t make myself understood, not in your world, the world of bodies, of tongues and fingers; and most of the time I have no listeners, not on your side of the river. Those of you who may catch the odd whisper, the odd squeak, so easily mistake my words for breezes rustling the dry reeds, for bats at twilight, for bad dreams.

But I’ve always been of a determined nature. Patient, they used to call me. I like to see a thing through to the end.

-

It’s dark here, as many have remarked. ‘Dark Death’, they used to say. ‘The gloomy halls of Hades’, and so forth. Well, yes, it is dark, but there are advantages – for instance, if you see someone you’d rather not speak to you can always pretend you haven’t recognised them.

There are of course the fields of asphodel. You can walk around in them if you want. It’s brighter there, and a certain amount of vapid dancing goes on, though the region sounds better than it is – the fields of asphodel has a poetic lilt to it. But just consider. Asphodel, asphodel, asphodel – pretty enough white flowers, but a person gets tired of them after a while. It would have been better to supply some variety – an assortment of colours, a few winding paths and vistas and stone benches and fountains. I would have preferred the odd hyacinth, at least, and would a sprinkling of crocuses have been too much to expect? Though we never get spring here, or any other seasons. You do have to wonder who designed the place.

Have I mentioned the fact that there’s nothing to eat except asphodel?

But I shouldn’t complain.

The darker grottoes are more interesting – the conversation there is better, if you can find a minor rascal of some sort – a pickpocket, a stockbroker, a small-time pimp. Like a lot of goody-goody girls, I was always secretly attracted to men of that kind.

I don’t frequent the really deep levels much, though. That’s where the punishments are dealt out to the truly villainous, those who were not sufficiently punished while alive. It’s hard to put up with the screams. The torture is mental torture, however, since we don’t have bodies any more. What the gods really like is to conjure up banquets – big platters of meat, heaps of bread, bunches of grapes – and then snatch them away. Making people roll heavy stones up steep hills is another of their favourite jests. I sometimes have a yet to go down there: it might help me to remember what it was like to have real hunger, what it was like to have real fatigue.

Every once in a while the fogs part and we get a glimpse of the world of the living. It’s like rubbing the glass on a dirty window, making a space to look through. Sometimes the barrier dissolves and we can go on an outing. Then we get very excited, and there is a great deal of squeaking.

These outings can take place in many ways. Once upon a time, anyone who wished to consult us would slit the throat of a sheep or cow or pig and let the blood flow into a trench in the ground. We’d smell it and make a beeline for the site, like flies to a carcass. There we’d be, chirping and fluttering, thousands of us, like the contents of a giant wastepaper basket caught in a tornado, while some self-styled hero held us off with drawn sword until the one he wanted to consult appeared. A few vague prophecies would be forthcoming: we learned to keep them vague. Why tell everything? You needed to keep the coming back for more, with other sheep, cows, pigs, and so forth.

Once the right number of words had been handed over to the hero we’d all be allowed to drink from the trench, and I can’t say much in praise of the table manners on such occasions. There was a lot of pushing and shoving, a lot of slurping and spilling; there were a lot of crimson chins. However, it was glorious to feel the blood coursing in our non-existent veins again, if only for an instant.

We could sometimes appear as dreams, though that wasn’t as satisfactory. Then there were those who got stuck on the wrong side of the river because they hadn’t been given proper burials. They wandered around in a very unhappy state, neither here nor there, and they could cause a lot of trouble.

Then after hundreds, possibly thousands of years – it’s hard to keep track of time here, because we don’t have any of it as such – customs changed. No living people went to the underworld much any more, and our own abode was upstaged by a much more spectacular establishment down the road – fiery pits, wailing and gnashing of teeth, gnawing worms, demons with pitchforks – a great many special effects.

But we were still called up occasionally by magicians and conjurors – men who’d made pacts with the infernal powers – and then by smaller fry, the table-tilters, the mediums, the channellers, people of that ilk. It was demeaning, all of it – to have to materialise in a chalk circle or a velvet-upholstered parlour just because someone wanted to gape at you – but it did allow us to keep up with what was going on among the still-alive. I was very interested in the invention of the light bulb, for instance, and in the matter-into-energy theories of the twentieth century. More recently, some of us have been able to infiltrate the new ethereal-wave system that now encircles the globe, and to travel around that way, looking out at the world through the flat, illuminated surfaces that serve as domestic shrines. Perhaps that’s how the gods were able to come and go as quickly as they did back then – they must have had something like that at their disposal.

I never got summoned much by the magicians. I was famous, yes – ask anyone – but for some reason they didn’t want to see me, whereas my cousin Helen was much in demand. It didn’t seem fair – I wasn’t known for doing anything notorious, especially of a sexual nature, and she was nothing of not infamous. Of course she was very beautiful. It was claimed she’d come out of an egg, being the daughter of Zeus who’s raper her mother in the form of a swan. She was quite stuck-up about it, was Helen. I wonder how many of us really believed that swan-rape concoction? There were a lot of stories of that kind going around then – the gods couldn’t seem to keep their hands or paws or beaks off mortal women, they were always raping someone or other.

Anyway, the magicians insisted on seeing Helen, and she was willing to oblige. It was like a return to the old days to have a lot of men gawping at her. She like to appear in one of her Trojan outfits, over-decorated to my taste, but chacun à son gout. She had a kind of slow twirl she would do; then she’d lower her head and glance up into the face of whoever had conjured her up, and give one of her trademark intimate smiles, and they were hers. Or she’d take on the form in which she displayed herself to her outraged husband, Menelaus, when Troy was burning and he was about to plunge his vengeful sword into her. All she had to do was bare one of her peerless breasts, and he was down on his knees, and drooling and begging to take her back.

As for me… well, people told me I was beautiful, they had to tell me that because I was a princess, and shortly after that a queen, but the truth was that although I was not deformed or ugly, I was nothing special to look at. I was smart, though: considering the times, very smart. That seems to be what I was known for: being smart. That, and my weaving, and my devotion to my husband, and my discretion.

If you were a magician, messing around in the dark arts and risking your soul, would you want to conjure up a plain but smart wife who’d been good at weaving and had never transgressed, instead of a woman who’d driven hundreds of men mad with lust and had caused a great city to go up in flames?

Neither would I.

Helen was never punished, not one bit. Why not, I’d like to know? Other people got strangled by sea serpents and drowned in storms and turned into spiders and shot with arrows for much smaller crimes. Eating the wrong cows. Boasting. That sort of thing. You’d think Helen might have got a good whipping at the very least, after all the harm and suffering she caused to countless other people. But she didn’t.

Not that I mind.

Not that I minded.

I had other things in my life to occupy my attention.

Which brings me to the subject of my marriage.

-

we had no voice

we had no name

we had no choice

we had one face

one face the same

we took the blame

it was not fair but now we’re here

we’re all here too

the same as you

and now we follow

you, we find you

now, we call

to you to you

too wit too woo

too wit too woo

too woo

A. E. Stallings ‘The Wife of the Man of Many Wiles’, Archaic Smile (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)

-

Believe what you want to. Believe that I wove,

If you wish, twenty years, and waited, while you

Were knee-deep in blood, hip-deep in goddesses.

I’ve not much to show for twenty years’ weaving—

I have but one half-finished cloth at the loom.

Perhaps it’s the lengthy, meticulous grieving.

Explain how you want to. Believe I unravelled

At night what I stitched in the slow siesta,

How I kept them all waiting for me to finish,

The suitors, you call them. Believe what you want to.

Believe that they waited for me to finish,

Believe I beguiled them with nightly un-doings.

Believe what you want to. That they never touched me.

Believe your own stories, as you would have me do,

How you only survived by the wise infidelities.

Believe that each day you wrote me a letter

That never arrived. Kill all the damn suitors

If you think it will make you feel better.

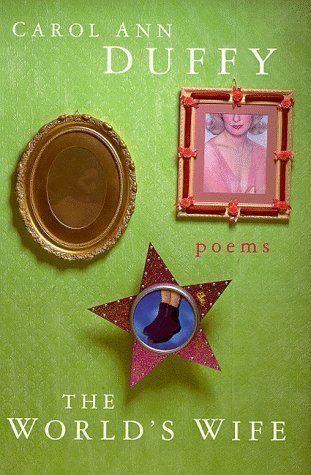

Carol Ann Duffy ‘Penelope’, The World’s Wife (Picador, 1999)

-

…..

And when the others came to take his place,

disturb my peace,

I played for time.

I wore a widow’s face, kept my head down,

did my work by day, at night unpicked it.

I knew which hour of the dark the moon

would start to fray,

I stitched it.

Grey threads and brown

pursued my needle’s leaping fish

to form a river that would never reach the sea.

I tried it. I was picking out

the smile of a woman at the centre 40

of this world, self-contained, absorbed, content,

most certainly not waiting,

when I heard a far-too-late familiar tread outside the door.

I licked my scarlet thread

and aimed it surely at the middle of the needle’s eye once more.

Hannah Khalil ‘Penelope: Watching the Grass Grow’, 15 Heroines: The War / The Desert / The Labyrinth (Jermyn Street Theatre 2020)

Like Penelope’s Web itself, these theatre scripts emerged from the Covid-19 lockdown. ‘15 Monologues adapted from Ovid’ are 15 free adaptations of Ovid’s Heroides (see above), all written by female playwrights.

Hannah Khalil, a Palestinian-Irish playwright, responds to Penelope’s letter to Odysseus. In Khalil’s ‘Penelope: Watching the Grass Grow’ we see another acerbic Penelope reflect on the absence of her husband - who has been missing for a week on a ‘work jolly’. This Penelope is firmly rooted in the twenty-first century, hovering over her mobile phone and reflecting on how many voicemails and texts she has sent without hearing back from her husband. She reflects on the communities of WhatsApp, on her husband’s ability to get to an internet cafe, on the second hand reports she is getting on Odysseus’ team-building shenanigans. She also has to fend off the attentions of the next-door neighbour, and comes up with a decisive - if not subtle - way to stop him mowing her lawn.

Find out more about the first performance of this work here, or buy the book of all the scripts here.

Hannah Khalil

-

…..

Six days you said, six. Works outing. Team building. Network. Make connections. But connection with who?

I fear that insanely too.

Foreign love.

Flame-haired beauties.

Ridiculous. Insane. And yet. Why not?

It’s not only men over there is it? Where you are. And we’re not unattractive either… And people notice. Don’t they?

A beat.

Like Mel next door. He keeps asking where you are - I told him away - work - back soon. But he’s counting the days too. Keeps ‘checking in’… from a distance of course. And Geoff opposite keeps twitching his curtains ever time I put out the rubbish. I’m watched. And I’m getting sick of it.

A beat.

You know I woke up yesterday to the sound of lawnmower Outside the window and it was him. Mel.

Mowing our lawn.

Your lawn.

I was so shocked I leaned out of the window in my nightie.

Half-asleep. Didn’t know what was going on. He got an eyeful. Rather pleased about it I think. I ran to get my dressing gown. Went outside in my slippers. ‘What are you doing?’

That’s my lawn.

His lawn.

His job.

‘I was doing my own,’ he says. ‘And thought yours needed a bit of attention – no trouble,’ he says.

No trouble.

And he eyes my dressing-gown cord. From a distance. And says, ‘He is coming back isn’t he?’ And I say ‘YES YES HE IS COMING BACK.’ ‘But it’s been more than a week now hasn’t it?’ he says, and I want to punch him in the face because I don’t want him on my lawn – our lawn counting, counting days that you have been absent – away from me.

Ciaran Walsh for CIWA Design

Gareth Hinds The Odyssey (Candlewick Press, 2010)

This is a recent graphic novel adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey. The artist describes how he set about the work:

‘Luckily The Odyssey is a rather fantastic story, so I didn’t feel I needed to be one-hundred-percent historically accurate. In fact, after researching the history pretty thoroughly, I opted to break from realism in most of my designs, while preserving just enough historical touches to give Odysseus’s world a ring of authenticity.’

Spotify playlist

Click on the button for an ever-growing playlist of music inspired by Penelope’s story.